Cracking a skill-specific interview, like one for Character Blocking and Staging, requires understanding the nuances of the role. In this blog, we present the questions you’re most likely to encounter, along with insights into how to answer them effectively. Let’s ensure you’re ready to make a strong impression.

Questions Asked in Character Blocking and Staging Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between ‘blocking’ and ‘staging’.

While often used interchangeably, ‘blocking’ and ‘staging’ have distinct meanings in theatre. Blocking refers to the precise physical movements of actors on stage – their entrances, exits, crosses, and interactions with each other and the set. It’s the choreography of the actors’ bodies. Staging, on the other hand, encompasses the broader picture, including the overall spatial arrangement of elements on the stage: actors, sets, props, and lighting. Think of blocking as the dance steps and staging as the entire dance composition.

For example, blocking might dictate that an actor walks from upstage center to downstage right, picks up a letter, and then turns to address another actor. Staging would consider the overall placement of furniture and how the lighting highlights this interaction.

Q 2. Describe your process for creating believable character movement.

Creating believable character movement begins with a deep understanding of the character’s personality, motivations, and relationships. I start by analyzing the script, paying close attention to subtext and implied actions. Then, I brainstorm potential physical manifestations of those inner lives. Is the character anxious? Their movements might be fidgety and quick. Is the character powerful? Their movements might be slow, deliberate, and expansive.

I work closely with actors, encouraging them to embody the character physically. We might use improvisation exercises to explore different movement options. I look for consistency – does the character’s posture reflect their emotional state? Are their gestures natural and authentic to their personality? The goal is to ensure every movement tells a story and reinforces the character’s arc.

For example, in a scene where a character is secretly plotting revenge, their movements might be furtive and clandestine – glancing over their shoulder, whispering, quickly concealing objects. Contrast this with a character experiencing grief – their movements might be slow, heavy, and slumped.

Q 3. How do you use blocking to enhance the storytelling?

Blocking is a powerful storytelling tool. It can create tension, reveal character relationships, and heighten emotional moments. Consider the use of proximity: actors standing close together can suggest intimacy or conflict, while distance can represent isolation or animosity. The direction of movement also matters; a character moving towards another suggests engagement, while moving away suggests withdrawal or rejection.

For instance, in a confrontation scene, strategically placing actors so they face off directly creates immediate visual tension. Alternatively, using a cross or a series of movements to subtly shift power dynamics within a scene adds another layer of storytelling. A character strategically moving to stand upstage of another subtly visually conveys dominance.

Q 4. How do you incorporate practical considerations (set design, props) into your blocking?

Practical considerations are paramount in blocking. The set design dictates the possibilities and limitations of movement. A cramped set will necessitate different blocking than a spacious one. Props also play a role; blocking must account for how actors interact with and move around props without disrupting the flow of the scene. I carefully study the set design and prop list before beginning the blocking process, ensuring that the actors’ movements are both effective and safe.

For example, if the set features a large, imposing table, the blocking might involve actors circling it, strategically positioning themselves to show dominance or subordination. If a prop is fragile, the blocking will need to accommodate this to avoid accidental damage or injury.

Q 5. Explain your approach to working with actors on finding their physicality in a role.

Helping actors find their physicality is a collaborative process. I begin by discussing the character’s background, motivations, and relationships. We explore physical exercises to unlock movement choices appropriate to the character’s emotional state and history. This might include exploring various postures, gestures, and walks, and connecting these to the character’s inner world. I encourage experimentation and offer feedback, gently guiding actors to discover truthful and consistent physical choices.

I might use sensory exercises – asking actors to imagine the textures of the clothes they are wearing, the temperature of the environment, or the weight of an object they are holding – to help them connect physically with the role. We’ll also consider the overall movement style of the production – is it naturalistic, stylized, or something in between? This helps to ensure consistency and unity across the performances.

Q 6. How do you handle conflicts between actor preferences and your vision for the blocking?

Conflicts between actor preferences and my vision are inevitable, but they are opportunities for creative collaboration. I begin by listening attentively to the actor’s concerns and ideas, understanding their rationale. Often, a compromise can be found that integrates the actor’s input while still serving the overall staging and storytelling. The goal is to create a mutually beneficial solution that allows the actor to perform authentically while meeting the directorial vision.

Sometimes, I’ll suggest alternative movements that achieve a similar effect but better suit the production’s style or the technical aspects of the set. The conversation emphasizes a shared goal – telling the best possible story through compelling movement and performance.

Q 7. How do you create a sense of rhythm and pace through blocking?

Rhythm and pace in blocking are crucial for maintaining audience engagement. Fast-paced movements can heighten tension or convey excitement, while slow, deliberate movements can create suspense or underscore emotional weight. I create this rhythm by varying the speed and intensity of actors’ movements. Pauses, strategically placed, create impact and allow audiences to absorb key moments. The overall tempo of the blocking should reflect the emotional arc of the scene and the play as a whole.

For instance, a comedic scene might feature quick, energetic movements and snappy dialogue delivery, while a tragic scene might rely on slower, more deliberate movements and pauses between lines. Careful attention to transitions between moments is crucial for maintaining a consistent flow and preventing a choppy or disjointed feel.

Q 8. Describe a time you had to adapt your blocking due to unforeseen circumstances.

Adapting blocking due to unforeseen circumstances is a crucial skill. It often involves creative problem-solving and a flexible approach. For example, during a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, we discovered a significant structural issue with a set piece – a crucial tree was unstable. Our initial blocking relied heavily on the actors interacting with this tree. Instead of scrapping the entire blocking, we held a quick rehearsal, brainstorming alternative positions. We re-imagined the scene’s flow, using the space around the unstable tree, emphasizing other set elements like strategically placed rocks to mimic the tree’s function as a central point. This involved adjusting entrances and exits, re-positioning key moments to maintain the emotional arc and the overall pacing. We also worked with the lighting designer to subtly highlight the alternative focal points, thus drawing the audience’s attention to the redesigned interactions.

The key was open communication and a willingness to improvise. We explained the situation to the actors, involving them in the process of re-blocking, making them feel empowered to find creative solutions. This collaborative problem-solving resulted in a seamless performance despite the unexpected challenge. This taught me the importance of having a flexible blocking plan that allows for adjustments while still adhering to the director’s vision.

Q 9. How do you use levels and proximity to create visual interest and emotional impact?

Levels and proximity are powerful tools for visual storytelling and emotional impact. Levels refer to the vertical placement of actors on stage – high, middle, or low. Proximity refers to how close or far actors are from each other and from the audience. A character positioned on a raised platform might convey dominance or isolation, while a character kneeling demonstrates vulnerability. Conversely, close proximity between characters suggests intimacy, conflict, or shared experience, whereas distance might indicate alienation or suspicion.

For instance, in a scene depicting a tense confrontation, placing the characters at opposite ends of the stage, utilizing the full depth of the playing area, can effectively heighten the tension. As the conflict escalates, gradually moving them closer creates palpable anticipation and a feeling of escalating drama. The use of levels adds another layer—one character might stand tall, emphasizing their authority, while the other might crouch down, emphasizing their fear or submission. Conversely, a scene requiring tenderness or intimacy would use close proximity, often on a lower level to create a sense of vulnerability and connection.

Q 10. How do you ensure the blocking doesn’t distract from the dialogue or action?

Blocking should never overshadow the dialogue or action; it should enhance them. The key is to keep the movement purposeful and motivated. Each movement should have a reason—to emphasize a line, reveal emotion, or highlight a relationship. Avoid unnecessary fidgeting or pacing that distracts the audience from the story.

Before rehearsals, I carefully analyze the script to pinpoint key emotional beats and dramatic moments. This informs my initial blocking ideas. During rehearsals, I observe the actors’ performances, making adjustments to ensure the blocking supports their interpretations and doesn’t interfere with their delivery or expression. Regularly I ask myself: ‘Does this movement add to the scene or detract from it?’ If the answer is the latter, I change it. A good rule of thumb is ‘less is more’—often simple, elegant movements are far more effective than complex, distracting ones.

Q 11. Describe your process for creating a stage picture.

Creating a stage picture involves visualizing the overall composition of actors on stage at any given moment. It’s like framing a photograph. My process begins with a deep understanding of the script’s narrative and subtext. I then consider the relationships between characters, their emotional states, and the overall mood of the scene.

My approach is iterative. I start by mapping out potential positions for key moments, considering levels, proximity, and stage areas (upstage, downstage, center stage, etc.). Then, I work with the actors to refine these positions, ensuring they feel natural and expressive within the context of the scene. Throughout this process, I’m constantly reviewing the stage picture to ensure it is visually interesting and complements the story. I’ll often use floor plans and drawings to help visualize the overall composition, making changes as needed throughout rehearsals.

Q 12. How do you utilize the space effectively, considering sightlines and audience perspective?

Effective space utilization is paramount. It involves considering sightlines (what the audience can see) and ensuring every actor is visible and accessible to the audience. I begin by analyzing the stage’s shape and size, identifying any potential challenges, such as pillars or awkward corners. I then consider the audience’s perspective – where they are sitting and what angles provide the best view.

For instance, if the stage is thrust (extends into the audience), I might use that space to create intimate moments with specific characters. I would then balance those intimate moments with wider compositions that showcase all the actors in a scene. Maintaining a balance between intimacy and visibility is key. I utilize the full stage depth and width to prevent actors from clustering in one area and to provide visual variety. Regularly checking sightlines from various audience positions is crucial to ensure clear and engaging viewing for everyone.

Q 13. How do you incorporate stage combat or other physical action into your blocking?

Incorporating stage combat or physical action requires close collaboration with a fight choreographer or movement specialist. Safety is the utmost priority. Before integrating any fight choreography into the blocking, we work closely with the actors to ensure they are properly trained and comfortable with the movements. We choreograph the fights to be both visually exciting and narratively appropriate, making sure it serves the story and doesn’t overshadow the emotional content of the scene.

The blocking must accommodate the fight choreography without compromising the flow of the scene. This might involve carefully planning entrances and exits, adjusting the positions of other actors during the fight, and using stage space strategically to give the fight a sense of scale and impact. Incorporating fight choreography into the blocking necessitates a meticulous approach that prioritizes safety and narrative integration. The fight must have a clear purpose within the dramatic arc and be visually compelling for the audience.

Q 14. How do you work with the lighting designer to enhance the blocking?

Collaboration with the lighting designer is essential. Lighting can dramatically enhance the blocking, emphasizing key moments and creating atmosphere. Early discussions with the lighting designer are critical—ideally before rehearsals even begin. I share the blocking plan with the lighting designer, discussing how lighting can highlight key stage pictures, create mood, and focus the audience’s attention on specific actors or actions.

For instance, specific lighting cues can emphasize the transition from one scene to another. A spotlight on a single actor can heighten their emotional impact during a monologue. Lighting can also be used to subtly guide the audience’s eye from one area of the stage to another, supporting the flow of the blocking. Open communication with the lighting designer ensures that the lighting complements the blocking, creating a cohesive and visually stunning production.

Q 15. How do you use blocking to create a sense of place and time?

Blocking, the precise arrangement of actors on stage, is a powerful tool for establishing place and time. We can use it to suggest the size and shape of a space, the era the scene is set in, and even the mood.

- Space: A cramped arrangement suggests a small, intimate setting like a crowded train car, while actors spread widely across the stage imply a vast open space like a battlefield. For example, a scene set in a tiny attic might see actors constantly bumping into furniture or each other, creating a palpable sense of confinement.

- Time: The pace of movement, the formality of posture, and even the use of props can inform the audience about the time period. Rapid movements and informal postures might suggest a modern setting, whereas slow, deliberate movements and formal poses could indicate a period piece. Consider a scene set in a bustling 1920s speakeasy; quick, energetic movements and a close physical proximity between characters would reinforce that era’s feel.

- Mood: The overall arrangement of actors can set the emotional tone of a scene. A scene filled with tension might have actors positioned in a confrontational manner, facing each other directly. Alternatively, a peaceful, reflective scene could feature actors positioned further apart, perhaps gazing out at the audience or into the distance.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. How do you balance the need for structure with allowing for improvisation?

Balancing structure with improvisation requires careful planning and a flexible approach. A solid blocking plan acts as a roadmap, ensuring the scene flows logically and visually. However, leaving room for spontaneity keeps the performance fresh and engaging.

- Pre-blocking: I typically start with a detailed blocking plan, mapping out key moments and relationships. This ensures a strong foundation for the actors to work from.

- Rehearsals: During rehearsals, I encourage actors to experiment within the parameters of the initial plan. I might suggest alternative positions or movements, exploring different ways to convey the same message or emotional arc. This iterative process allows for organic improvisation while still maintaining the scene’s overall structure.

- Trust: A strong rapport with the actors is crucial. I need to create an environment where they feel comfortable experimenting and making adjustments. The emphasis isn’t on rigid adherence to the plan, but rather on achieving the desired impact creatively. I often use the analogy of a river: The initial plan is the riverbed, providing structure, but the flow of the performance, informed by the actors’ intuition, is like the water that moves naturally within that structure.

Q 17. Explain your approach to blocking ensemble scenes.

Blocking ensemble scenes presents unique challenges, requiring careful consideration of group dynamics and individual character arcs. I use a combination of strategies to manage the complexity.

- Establish Key Relationships: I start by identifying the primary relationships within the scene. Which characters are in conflict? Which ones are allies? The initial blocking will reflect these core relationships.

- Use Stage Areas Effectively: I aim for dynamic use of the entire stage, avoiding congestion in one area. I may assign specific stage areas to particular characters or groups, allowing for clear visual distinctions and preventing overlaps.

- Create Visual Focus: In a busy ensemble scene, it’s essential to create a visual focal point that draws the audience’s attention where it needs to be. This could be achieved through staging, lighting or even using a specific prop as a central point of interest.

- Movement Patterns: I coordinate the actors’ movements to create a sense of flow and energy. Avoid static arrangements, encouraging purposeful movement that enhances the dialogue and the overall narrative.

Q 18. Describe how you collaborate with other creative teams (costume, sound, etc.) on blocking.

Collaboration is key to successful blocking. I work closely with costume, sound, and lighting designers to ensure everything is cohesive and supports the overall vision.

- Costume: The costume design influences movement. Restrictive clothing or elaborate costumes will affect how an actor moves, which should inform my blocking choices. For example, a character in a large, flowing gown might require more space and careful maneuvering than a character in simple attire.

- Sound: Sound cues, music, or sound effects can be integrated into the blocking to enhance emotional impact and timing. For instance, a sudden loud sound might trigger a specific reaction or movement from the actors.

- Lighting: I work with the lighting designer to ensure the blocking highlights key moments and relationships. Lighting can focus attention on a particular character or group, enhancing the impact of their movements and interactions.

Q 19. How do you use blocking to develop character relationships?

Blocking is an effective tool for subtly portraying character relationships. The physical distance between actors, their body language, and their relative positions on stage all communicate their dynamic.

- Proximity: Close proximity suggests intimacy, while distance may indicate conflict or estrangement. A character positioned upstage, away from the others, might be isolated or marginalized.

- Body Language: The angle of an actor’s body and their gestures, informed by the blocking, also reveals relationships. Facing directly toward another character suggests engagement, while turned away might signal disinterest or hostility.

- Blocking to support dialogue: Clever blocking can support what is happening in the dialogue. For instance, two characters arguing might be positioned in a confrontational manner, moving closer and further apart in tandem with the intensity of the argument.

Q 20. How do you create a clear and concise blocking plan for a production?

A clear blocking plan should be concise, visually accessible, and easy to follow for both the director and the actors.

- Ground Plan: I use a ground plan (a bird’s-eye view of the stage) to map out actor positions at key moments in the scene. Simple symbols represent each character, and numbers indicate the sequence of actions.

- Detailed Notes: Alongside the ground plan, I write detailed notes specifying entrances, exits, significant gestures, and interactions between characters. This ensures consistency and understanding.

- Rehearsal Notes: I keep detailed notes of any changes or adjustments made during rehearsals, updating the plan accordingly. This dynamic document evolves alongside the creative process.

- Sharing the Plan: The plan should be distributed to the actors and other relevant members of the creative team. This ensures everyone is on the same page, fostering collaboration and reducing confusion.

Q 21. What are some common mistakes to avoid when blocking a scene?

Several common mistakes can hinder the effectiveness of blocking. Avoiding these pitfalls is crucial for a successful production.

- Over-blocking: Too much movement can distract from the dialogue and the emotional core of the scene. Less is often more; aim for purposeful movement that supports the narrative rather than cluttering it.

- Ignoring the Audience: The blocking should consider the audience’s perspective. Avoid having actors’ backs constantly turned to the audience or blocking crucial moments behind scenery.

- Inconsistent Movement: Movement should be motivated and believable. Avoid jerky or unnatural movements that disrupt the flow of the scene.

- Ignoring Character Relationships: The blocking should reflect the relationships between characters. Failing to utilize space and position to communicate these dynamics weakens the scene’s overall impact.

- Not Leaving Room for Improvisation: While a solid plan is vital, rigidity can stifle creativity. Allow some space for improvisation during rehearsals to keep the performance fresh and engaging.

Q 22. How do you ensure the blocking is safe for actors?

Actor safety is paramount in blocking. My process begins with a thorough risk assessment of the planned movements. This involves considering the set design – are there potential hazards like low-hanging objects, uneven flooring, or precarious props? I also assess the actors themselves; are there any physical limitations or injuries I need to be aware of?

For instance, if an actor needs to quickly traverse a narrow space, I’d ensure there’s ample room and potentially add extra padding or staging elements to prevent slips or falls. If an actor has a knee injury, I’ll avoid any movements that put undue stress on that joint, adapting the blocking to accommodate their limitations. Clear communication with the actors is vital – I always discuss any potential risks and solicit their feedback. We collaborate to find solutions that are both dramatically effective and safe for everyone involved.

Q 23. Describe your process for rehearsing and refining blocking.

Rehearsing and refining blocking is an iterative process. It begins with an initial blocking session where we translate the director’s vision onto the stage. I usually start with the main action lines and key moments, creating a basic framework. We then work through scenes, adjusting the actor’s positions and movements based on their line readings and the emotional arc of the scene. I use a combination of verbal instruction, demonstration, and physical adjustments to guide the actors.

We videotape the rehearsals so we can review the progress and identify areas for improvement. During the refining stage, we concentrate on the details – refining entrances and exits, ensuring clear sightlines, and incorporating stage business that supports character and plot development. This often involves experimenting with different positions and rhythms to find what best serves the storytelling. This ongoing feedback loop, coupled with the video analysis, makes sure the blocking is not just safe but enhances the production’s overall impact.

Q 24. How do you handle technical issues that may affect the blocking?

Technical issues can significantly affect blocking. My approach is proactive and collaborative. I maintain constant communication with the technical director, set designer, and lighting designer throughout the process. For example, if a crucial set piece arrives late or is different than anticipated, we’ll hold a quick meeting to adapt the blocking accordingly. This might involve simplifying movements or re-arranging the spatial layout to accommodate the changes.

If lighting cues interfere with the planned movements, we work together to adjust the lighting plot or subtly alter the blocking to avoid conflict. Similarly, if sound cues necessitate specific actor positions, we integrate those requirements into the blocking early on. Flexibility and a willingness to problem-solve collaboratively are crucial when addressing technical challenges impacting the blocking.

Q 25. How do you approach blocking for different performance spaces (proscenium, thrust, arena)?

Blocking is fundamentally influenced by the performance space. In a proscenium theatre, the audience is on one side, which allows for more traditional blocking, using depth and perspective to create visual interest. Here, we might employ a strong downstage/upstage focus to build emotional intensity.

A thrust stage demands a more dynamic approach, using three-quarter or full circle movement to engage the audience across multiple sides. Blocking here considers sightlines from all angles. The arena stage, with the audience surrounding the performance area, requires very careful planning to avoid blocking actors from one another and to maintain consistent visibility for the entire audience. Circular or semi-circular movements can work well. Adaptability and a strong understanding of the different spatial dynamics are keys to successful blocking in any performance space.

Q 26. How do you use blocking to enhance the theme or message of the play?

Blocking isn’t just about where actors stand; it’s a powerful tool for reinforcing the play’s themes. For example, in a play about isolation, I might use blocking to physically separate characters, creating visual distance and mirroring their emotional disconnect. Conversely, in a play about unity, I’d strategically cluster characters together, creating a visual representation of their shared bond.

Movement can emphasize power dynamics. A dominant character might occupy the center stage, while a less powerful character might be positioned downstage, seemingly smaller and less significant. Careful use of levels (using steps, platforms) can enhance this effect. The tempo and style of movement can also reinforce thematic elements. Fast, frantic movements might suggest urgency or chaos, while slow, deliberate movements could suggest tension or reflection. By consciously aligning blocking with the thematic undercurrents of the play, we elevate the production to a richer and more impactful experience.

Q 27. Describe a challenging blocking problem you encountered and how you solved it.

In a recent production of ‘Hamlet’, we faced a challenge with a crucial scene involving a fight sequence and a complex set piece – a large, unwieldy throne. The original blocking placed the throne in a way that hampered the fight choreography and created awkward sightlines. The solution was a three-stage process.

First, we experimented with different throne positions, noting the pros and cons of each arrangement. Second, we revised the fight choreography to maximize safety and minimize the impact of the throne’s size. Finally, we worked with the technical crew to add a subtle, reversible change to the set piece that enabled us to clear space during specific moments in the fight. This collaborative approach, involving actors, fight choreographer, set designer, and myself, resulted in a dynamic fight scene while maintaining both dramatic intensity and actor safety.

Key Topics to Learn for Character Blocking and Staging Interview

- Understanding Space and Movement: Explore how character placement and movement on stage dictates narrative flow and audience engagement. Consider the impact of proximity, levels, and stage areas.

- Character Relationships Through Blocking: Analyze how blocking reveals relationships between characters. Discuss techniques for conveying power dynamics, intimacy, conflict, and connection through physical placement and movement.

- Creating a Visual Narrative: Learn how to use blocking to visually tell the story, emphasizing key moments and transitions. Consider the use of upstage and downstage, center stage, and other theatrical spaces to highlight emotional beats.

- Collaboration and Communication: Discuss the importance of effective communication with directors and actors in the blocking process. Explain how to receive and implement feedback constructively.

- Practical Application: Scene Analysis and Blocking Design: Practice analyzing a scene and designing effective blocking that enhances the storytelling. Consider the scene’s objectives, themes, and emotional arc.

- Problem-Solving in Blocking: Discuss challenges that might arise during blocking rehearsals and how to creatively solve them, considering technical limitations and actor limitations.

- Adaptability and Improvisation in Blocking: Explain the importance of adaptability in the blocking process, and how to adjust to unforeseen circumstances or actor preferences.

- Working with Different Production Styles: Demonstrate understanding of how blocking differs across various theatrical styles (e.g., realism, absurdism, musical theatre).

Next Steps

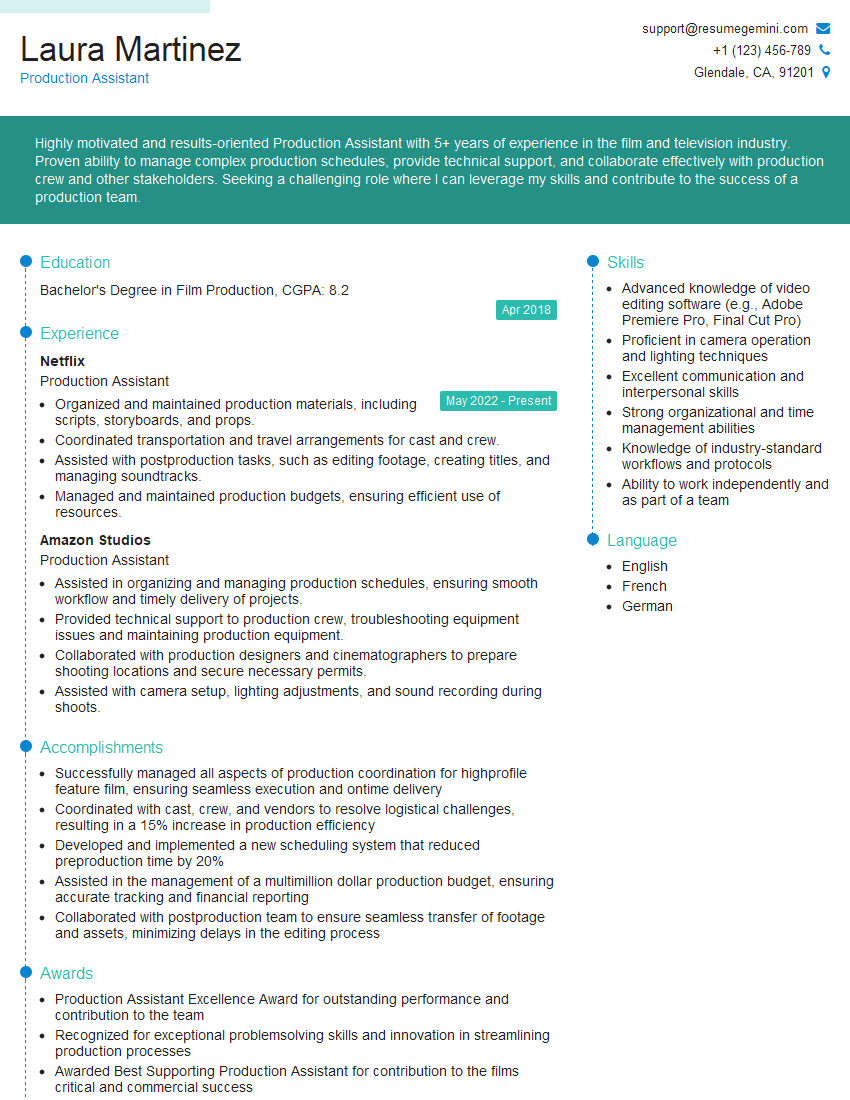

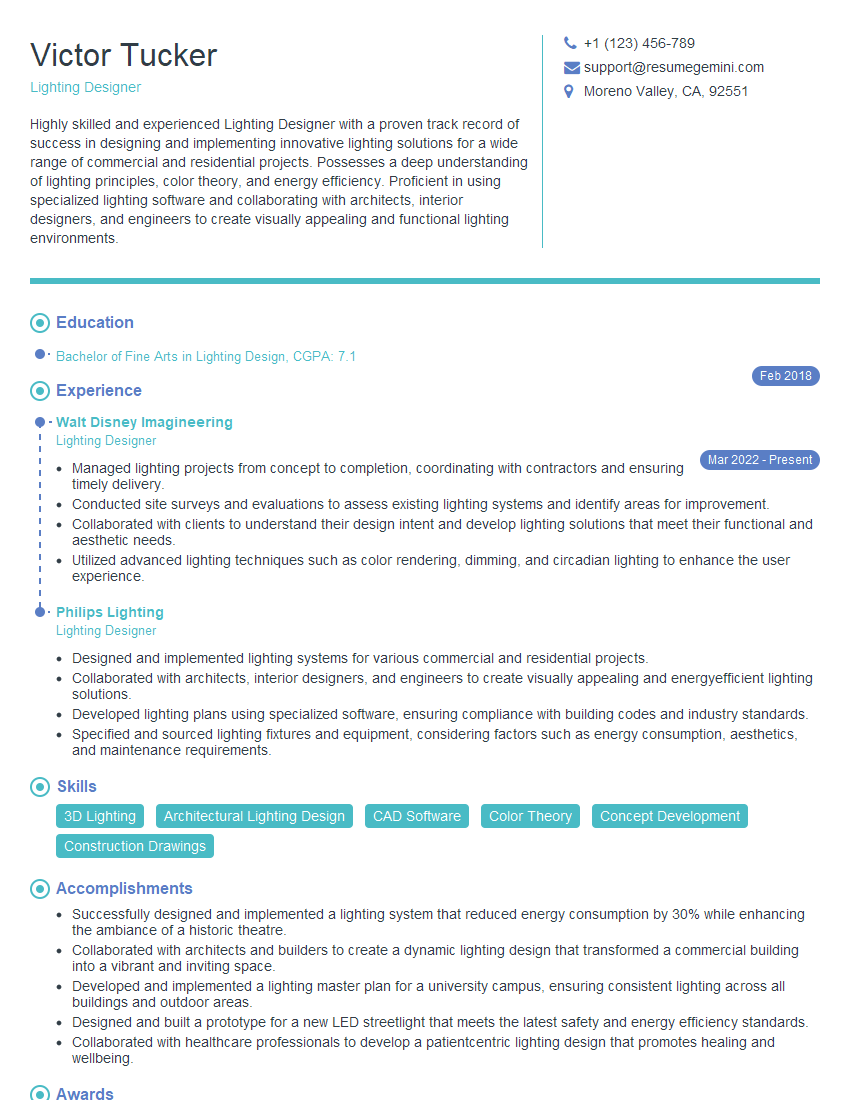

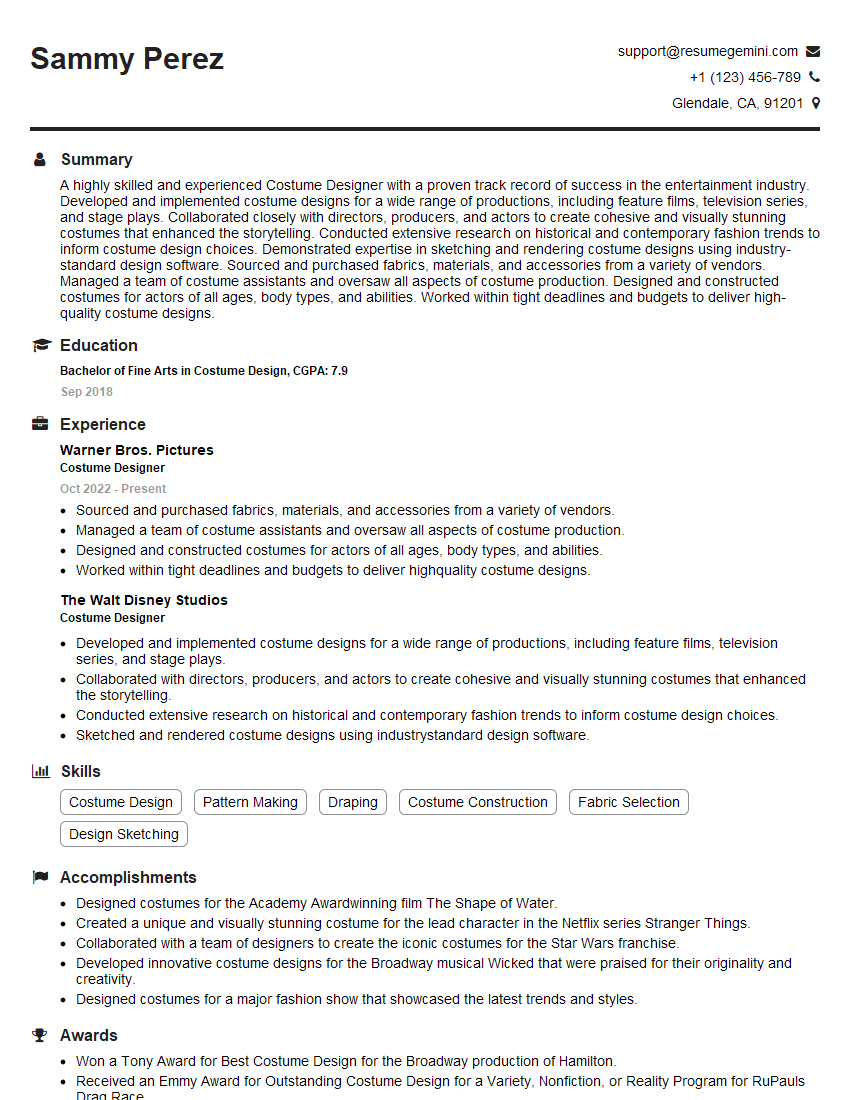

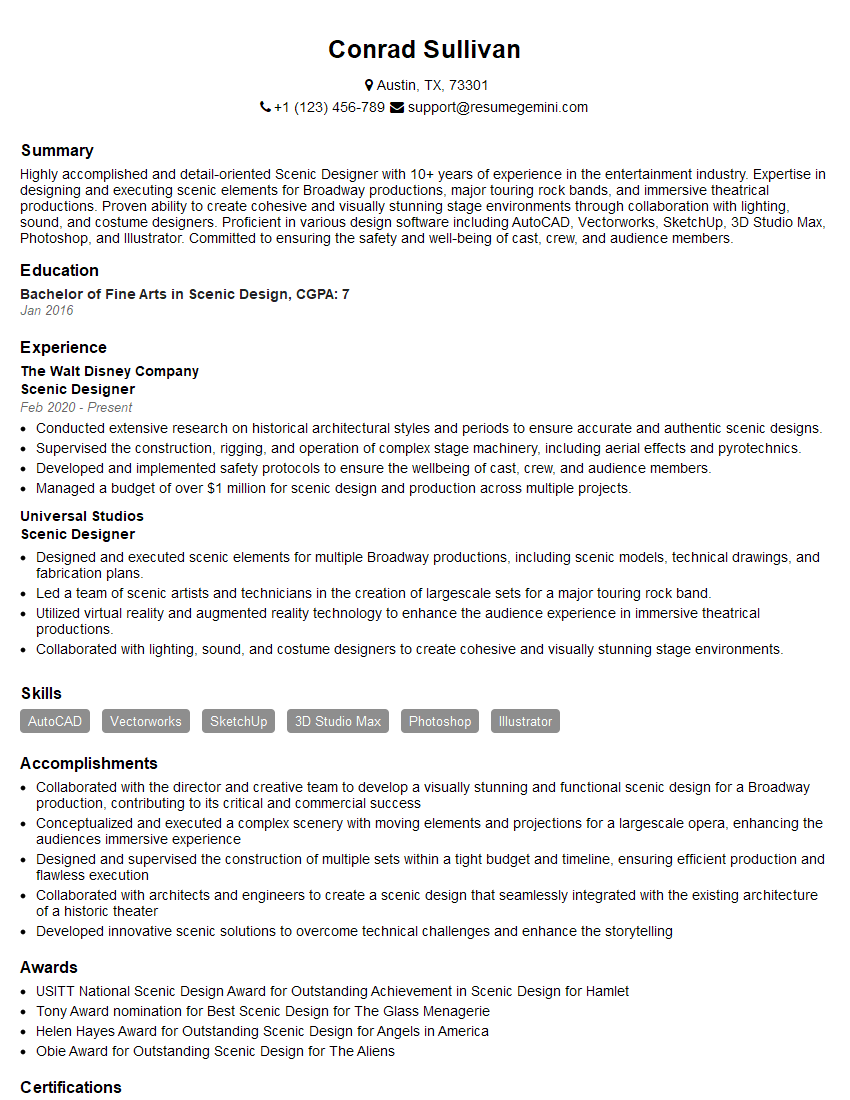

Mastering Character Blocking and Staging is crucial for career advancement in theatre, film, and television. A strong understanding of these skills demonstrates your ability to collaborate effectively, visually communicate narratives, and contribute significantly to a production’s success. To enhance your job prospects, create an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your skills and experience. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource to help you build a professional and impactful resume. Examples of resumes tailored to Character Blocking and Staging are available to help you get started.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

Interesting Article, I liked the depth of knowledge you’ve shared.

Helpful, thanks for sharing.

Hi, I represent a social media marketing agency and liked your blog

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?