Cracking a skill-specific interview, like one for Bioinformatics Databases (e.g., Ensembl, NCBI, UniProt), requires understanding the nuances of the role. In this blog, we present the questions you’re most likely to encounter, along with insights into how to answer them effectively. Let’s ensure you’re ready to make a strong impression.

Questions Asked in Bioinformatics Databases (e.g., Ensembl, NCBI, UniProt) Interview

Q 1. Explain the differences between Ensembl, NCBI, and UniProt databases.

Ensembl, NCBI, and UniProt are all invaluable bioinformatics databases, but they focus on different aspects of biological data. Think of them as complementary tools in a biologist’s toolbox.

Ensembl: Primarily focuses on vertebrate genomes, providing comprehensive annotation including gene predictions, regulatory regions, and variation data. It’s excellent for comparative genomics and studying gene function within a specific species’ context. Imagine Ensembl as a detailed map of a specific city, rich in information on individual buildings and their functions.

NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information): A broader resource encompassing numerous databases like GenBank (nucleotide sequences), PubMed (biomedical literature), and BLAST (sequence similarity search tool). It’s a vast repository of diverse biological information from various organisms and data types. Think of NCBI as a comprehensive atlas of the entire world, covering various geographical areas and providing diverse information sources.

UniProt: A central hub for protein information, providing a comprehensive, high-quality, and freely accessible resource of protein sequence and functional information. It integrates data from various sources and focuses on protein sequences, functions, structures, and interactions. UniProt is like a comprehensive encyclopedia of proteins, detailing their properties and functions across species.

In essence: Ensembl excels in genome annotation and comparative genomics; NCBI offers a broad range of biological data; and UniProt specializes in protein information.

Q 2. How would you search for a specific gene in Ensembl?

Searching for a specific gene in Ensembl is straightforward. Let’s say you want to find the TP53 gene (a crucial tumor suppressor gene) in humans. You’d typically use the Ensembl search bar, located prominently on the homepage.

You can search using several identifiers:

Gene name: Simply type ‘TP53’ into the search bar. This will typically bring up the human TP53 gene page.

Gene ID: If you know the Ensembl gene ID (e.g., ENSG00000141510), you can input that directly. This is more precise.

Other identifiers: You can also use other identifiers such as RefSeq IDs, HGNC symbols, or even synonyms for the gene.

Once you find the gene page, you’ll have access to a wealth of information, including sequence data, gene structure, expression patterns, orthologs, and related publications. Ensembl’s intuitive interface makes navigation easy.

Q 3. Describe the different data types available in UniProt.

UniProt provides a wealth of data types concerning proteins. Think of it as a protein’s detailed biography.

Sequence data: The core information—the protein’s amino acid sequence(s) in various formats (e.g., FASTA).

Functional information: Descriptions of the protein’s known functions, biological pathways involved, and associated molecular functions, often based on experimental evidence.

Structural information: Links to three-dimensional protein structure data from databases like PDB (Protein Data Bank), when available.

Post-translational modifications: Information about modifications like phosphorylation or glycosylation that alter the protein’s function.

Subcellular localization: Where the protein resides within a cell (e.g., nucleus, cytoplasm).

Cross-references: Links to related information in other databases like Ensembl, NCBI, and other specialized resources.

Literature references: Citations to scientific papers describing the protein’s characteristics and functions.

UniProt integrates data from multiple sources, ensuring high quality and comprehensive coverage. This integrated approach helps researchers understand a protein’s role in biological processes thoroughly.

Q 4. How do you handle inconsistencies or missing data in bioinformatics databases?

Inconsistencies and missing data are common challenges in bioinformatics databases due to the ever-evolving nature of biological knowledge and the diverse sources of data. Handling them requires a careful and systematic approach.

Data validation: Using various methods to assess data quality. This could include checking against other databases, using statistical methods, or performing experimental validation when possible.

Data integration: Combining data from multiple sources to reduce bias and fill data gaps. However, careful consideration must be given to potential discrepancies between sources.

Imputation techniques: For missing data, using statistical methods to predict missing values based on existing data. However, this should be done cautiously and transparently, as imputed values are not as reliable as directly observed data.

Careful interpretation: Being aware of the limitations of any particular database and being cautious when interpreting data from incomplete or potentially inconsistent sources. Always review the data sources and methodologies.

Contacting database curators: For serious inconsistencies or missing data, contacting the database curators directly might help resolve the issue or clarify ambiguities.

Think of it like a detective’s work: you collect clues from multiple sources, assess their reliability, and carefully draw conclusions, acknowledging areas of uncertainty.

Q 5. What are the different file formats commonly used in bioinformatics databases (e.g., FASTA, GFF, etc.)?

Bioinformatics databases utilize numerous file formats to store and exchange data efficiently. Each format has its own strengths and weaknesses.

FASTA: A simple text-based format for representing nucleotide or protein sequences. It starts with a ‘>’ symbol followed by a sequence identifier and then the actual sequence data on subsequent lines. Very common for representing sequences to be used in BLAST searches or other comparative analyses.

>sequence_name ATGCGT...GenBank: NCBI’s format for storing annotated nucleotide sequences. It is more complex than FASTA and contains additional information about the sequence, such as source organism, annotations, and experimental details.

GFF (General Feature Format): Used to describe the features of a genome (genes, exons, introns etc). It’s a tabular format specifying the location and type of features on a genome sequence.

chr1 . gene 1000 2000 . + . gene_id=gene1GTF (Gene Transfer Format): Similar to GFF but with minor differences in structure. It’s often used to represent gene models.

EMBL: Another widely used flat file format for sequence data very similar to GenBank.

BAM (Binary Alignment/Map): A binary format used to store sequence alignment data (like from an alignment to a reference genome).

Understanding these formats is crucial for processing and analyzing bioinformatics data efficiently.

Q 6. Explain the concept of homology and how it is used in database searches.

Homology refers to similarity between biological sequences (DNA, RNA, or protein) due to shared ancestry. It implies that sequences evolved from a common ancestor. Homology is the foundation of many database searches, enabling us to find similar sequences across species.

Imagine a family tree; homologous sequences are like relatives sharing similar features because of common ancestors. We can use the degree of sequence similarity to infer the evolutionary relationship between organisms.

In database searches, homology is leveraged using algorithms like BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool). BLAST compares a query sequence against a database, identifying sequences with statistically significant similarity, suggesting potential homology. The higher the similarity score (often expressed as E-value), the stronger the evidence for homology.

Q 7. How would you identify orthologous genes across different species using Ensembl?

Identifying orthologous genes across species using Ensembl involves utilizing its comparative genomics capabilities. Orthologs are genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene. Finding them helps understand conserved biological functions across evolution.

In Ensembl, you can typically find ortholog information on a gene’s detail page. Look for sections labeled ‘Homology’, ‘Orthologues’, or similar. Ensembl uses sophisticated algorithms to identify orthologs, often integrating data from multiple sources to improve accuracy.

For instance, after finding your gene of interest in a species (e.g., human TP53), the homology section will list predicted orthologs in other species, including their corresponding gene IDs in those species. You can then explore those orthologs to see their sequence similarity, genomic context and functional annotation in other organisms. This allows you to compare genes across evolutionary lines and learn about conserved pathways.

Q 8. Describe the different levels of annotation available in NCBI’s GenBank.

GenBank entries, the core data within NCBI’s nucleotide sequence database, contain multiple layers of annotation, providing a rich description of the sequence and its biological context. Think of it like building a house: you start with the foundation (the raw sequence), then add rooms (features), furnishings (annotations), and finally, the address (metadata).

Sequence Level: This is the fundamental layer – the raw nucleotide sequence itself. This is the base upon which all other annotations are built. It’s like the foundation of our house – without it, there’s nothing else.

Feature Table: This section describes various features within the sequence, such as genes, coding sequences (CDS), exons, introns, promoters, and regulatory regions. These are the ‘rooms’ of our house – defining the functional components.

Sequence Name and Accession Number: This unique identifier allows for easy retrieval and referencing of the sequence – like the address of the house.

Source Information: Details about the organism from which the sequence was derived – the ‘neighborhood’ of the house. This provides important biological context.

Publication Information: Links to scientific publications associated with the sequence – providing provenance and deeper information, akin to the property deed.

Cross-References: Connections to other databases, such as UniProt, providing additional data about the protein the gene encodes – equivalent to neighborly connections to other houses.

Functional Annotation: This layer uses information from various sources, including gene ontology (GO) terms and protein domain databases, to provide insights into the function of the gene product. This would be like the interior design – describing the purpose and use of each room.

The level of annotation varies depending on the quality and availability of data. Some entries have extensive functional annotation, while others may only include the basic sequence and feature information. For example, a newly sequenced genome might only have basic features annotated, while a well-studied gene from a model organism will have rich functional annotation.

Q 9. How can you use UniProt to determine the protein domains and functional motifs of a protein?

UniProt is a comprehensive resource for protein information. To find protein domains and functional motifs, you can utilize its various search and analysis tools. Imagine you’re a detective looking for clues about a protein’s identity and function. UniProt provides a wealth of evidence to help you solve the case.

Here’s how to do it:

Search for your protein: Use the UniProt accession number or the protein name to find your protein of interest. UniProt uses a sophisticated search engine – it’s like using a highly advanced search engine to find the specific file you need.

Check the ‘Domains and Sites’ section: This section shows predicted domains and functional sites in the protein sequence, using information from databases like InterPro. Think of these domains and sites as fingerprints or birthmarks unique to a protein, revealing its functionalities. It’s like finding the key clues you need to identify the suspect.

Explore cross-references: UniProt provides links to other databases such as Pfam, SMART, and ProSite. These databases specialize in protein domain and family classification. These are additional resources, providing additional lines of evidence for your protein investigation.

Examine the sequence features: Analyze the sequence itself, paying attention to regions marked as domains and motifs. This is like physically examining the suspect’s belongings to find more evidence.

For example, searching for ‘human p53′ will reveal multiple protein domains crucial to its function as a tumor suppressor. These domains’ annotation helps scientists understand how the protein functions in the cell.

Q 10. What are some common challenges in managing and querying large bioinformatics databases?

Managing and querying large bioinformatics databases present significant challenges. The sheer scale of data involved, often terabytes or even petabytes, demands sophisticated strategies and tools.

Data Storage and Retrieval: Efficient storage and retrieval systems are crucial. Relational databases (like those using SQL) might struggle with the scale and complexity, leading to slow query times. Distributed databases, NoSQL solutions, and cloud-based services can offer better scalability but come with their own complexity.

Data Heterogeneity: Data from various sources have different formats and structures, making integration and querying difficult. Harmonizing this information requires meticulous data cleaning, normalization, and standardized data models.

Data Volume and Velocity: The constantly increasing volume of data (new sequences, publications, experiments) and the speed at which it’s generated (high-throughput sequencing) requires adaptable and scalable solutions to keep up. It is like trying to keep up with a flood, constantly working to manage the overflow.

Query Optimization: Constructing efficient queries is paramount. Poorly written queries can take an unreasonable amount of time to execute on large datasets. Expert knowledge in database querying (SQL, NoSQL) and query optimization techniques is vital.

Data Consistency and Quality: Maintaining data quality and consistency is an ongoing challenge. Errors and inconsistencies can lead to inaccurate results. Rigorous quality control procedures, data validation, and data provenance tracking are essential.

For instance, integrating data from diverse sequencing projects requires dealing with different annotation standards and data formats, potentially leading to inconsistencies and requiring extensive pre-processing.

Q 11. Describe your experience with SQL or other database query languages in a bioinformatics context.

I have extensive experience using SQL (Structured Query Language) and other database query languages in a bioinformatics setting. My experience encompasses designing database schemas, writing complex queries, optimizing query performance, and working with various database management systems (DBMS).

I’ve used SQL to:

Retrieve specific genomic sequences based on criteria: For example, using

SELECT sequence FROM genes WHERE organism='human' AND gene_name='TP53'to get the TP53 gene sequence from a human genome database.Join data from different tables: Combining data on genes, proteins, and pathways using joins to perform comprehensive analysis, like

SELECT g.gene_name, p.protein_name, pw.pathway_name FROM genes g JOIN proteins p ON g.gene_id=p.gene_id JOIN pathways pw ON p.protein_id=pw.protein_id.Analyze gene expression data: Querying expression datasets (stored in relational or NoSQL databases) to identify differentially expressed genes under different conditions. This involves aggregation and complex filtering.

Create custom views and stored procedures: To simplify data access and enhance query performance.

Beyond SQL, I have experience with other languages such as Python with libraries like Pandas and biopython, which provide robust tools for data manipulation and querying of biological datasets that might not always fit into relational models neatly. This versatility allows for adaptation based on the task and data structure at hand.

Q 12. How would you validate the accuracy of data retrieved from a bioinformatics database?

Validating data retrieved from bioinformatics databases is crucial. Think of it like verifying the accuracy of a historical document; multiple sources are needed to corroborate the information. Here’s a multi-pronged approach:

Cross-referencing: Compare data from multiple databases. If information from UniProt, NCBI, and Ensembl all agree on a specific protein sequence, the confidence increases significantly. This is akin to checking multiple historical accounts to verify the facts.

Data source evaluation: Assess the quality and reliability of the source database. Reputable databases undergo rigorous quality control measures and provide detailed documentation. This is like verifying the credibility of the historical source.

Literature review: Check if the data aligns with published scientific literature. This adds another layer of validation and can highlight potential discrepancies or outdated information. It is like cross-referencing the information with other published works.

Computational validation: If possible, use computational methods to verify data. For example, aligning sequences to confirm homology or using protein structure prediction tools to verify domain predictions. This is like using scientific tools to verify the findings.

Statistical analysis: Analyze data for anomalies or outliers that might indicate errors. Statistical tests can reveal inconsistencies or unexpected patterns. This is like using mathematical analysis to verify the results.

For instance, if a database shows a gene with a particular function, checking for supporting publications and verifying the gene sequence against other trusted resources would reinforce the accuracy of the information.

Q 13. Explain your understanding of ontologies (e.g., GO) and their role in bioinformatics databases.

Ontologies, like the Gene Ontology (GO), are structured, controlled vocabularies that describe concepts within a specific domain. Think of them as highly organized dictionaries, offering a standardized way to describe biological entities and their relationships. In bioinformatics databases, ontologies play a vital role in enriching data annotation and enabling sophisticated queries. They are the organizational system of our data ‘library’.

GO, for example, provides a hierarchical structure describing gene products in terms of their associated biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Each term has a unique identifier and is linked to related terms, facilitating complex queries and analyses. It allows us to search for genes involved in a specific process, or explore the functional relationships between different genes. It is like a detailed cataloging system in a library; it allows us to locate books (genes) not just by title (gene name), but also by subject matter (function).

Ontologies are used in bioinformatics databases to:

Annotate gene products: Adding GO terms to genes provides a standardized description of their function and helps in integrating data from different sources.

Enable functional enrichment analysis: Identifying enriched GO terms in a set of genes provides insights into their collective functions and biological pathways.

Facilitate data integration and cross-referencing: Different databases can utilize ontologies to link related information, making it easier to perform complex analyses.

For instance, comparing two sets of genes using GO enrichment analysis can reveal functionally related genes that are differentially expressed between two conditions, assisting in understanding the biological mechanism.

Q 14. How would you identify potential protein-protein interactions using bioinformatics databases?

Identifying protein-protein interactions (PPIs) using bioinformatics databases involves integrating and analyzing information from multiple sources. This is akin to detective work, piecing together evidence from various sources to establish a connection between two individuals (proteins).

Methods include:

Literature mining: Manually or automatically searching scientific literature databases (PubMed) for publications reporting experimental evidence of PPIs. This is like reading crime scene reports to find clues.

Database searching: Using dedicated PPI databases (such as STRING, BioGRID) that curate experimentally verified or predicted interactions. These databases are like centralized evidence repositories, compiling information from multiple sources.

Phylogenetic analysis: Exploring evolutionary relationships between proteins. If two proteins consistently appear together across different species, this suggests a potential interaction. This is like examining the criminal’s history and social connections.

Network analysis: Analyzing the broader protein-protein interaction network to identify interacting proteins. This is like creating a social network map to visualize connections between suspects.

Sequence analysis: Searching for conserved protein domains that suggest a physical interaction or participation in the same pathway. This is like comparing fingerprints to determine if two suspects were at the crime scene together.

Combining evidence from multiple sources enhances confidence in predicted interactions. For example, identifying an interaction in STRING, supported by publications and sequence analysis, is much stronger evidence than a single prediction from a single method.

Q 15. Describe your experience using bioinformatics tools or pipelines that integrate with these databases.

My experience with bioinformatics tools and pipelines integrating with databases like Ensembl, NCBI, and UniProt is extensive. I’ve utilized various tools, including BioMart (for querying Ensembl), BLAST (for sequence similarity searches across NCBI databases), and the UniProt API for programmatic access to protein information. For example, I’ve built pipelines using Python and R, incorporating packages like biopython and rbioconductor to automate tasks such as downloading genomic sequences from Ensembl, performing BLAST searches against NCBI’s nucleotide database (nt), and then analyzing the results using statistical methods in R. This allowed for efficient and reproducible analysis across multiple species. Another project involved using the UniProt API to retrieve protein sequences and annotations for a specific protein family, then performing phylogenetic analysis on those sequences. This automated workflow saved considerable time and effort compared to manual data retrieval and analysis.

In a recent project focused on identifying potential cancer biomarkers, I leveraged BioMart to extract gene expression data from Ensembl, combined it with mutation data from a clinical database, and then employed machine learning techniques to predict potential biomarkers. The integration with Ensembl ensured reliable annotation and genomic context for the genes of interest.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. How would you approach troubleshooting errors encountered during database queries or analysis?

Troubleshooting database queries and analysis errors requires a systematic approach. My first step is to carefully examine the error message. This often reveals the root cause, such as a syntax error in a query, a missing database connection, or an issue with data formatting.

If the error message is unclear, I’ll check the query syntax meticulously. For instance, a small typo in a database query can lead to significant issues. I’ll test smaller parts of the query independently to isolate the problematic section. For API-based queries, validating inputs and checking the API documentation is crucial. If the problem persists, I’ll review the database schema to ensure I’m accessing the correct tables and columns.

If the error relates to data processing, I carefully check data types and formats. Inconsistencies can cause unexpected problems during analysis. Often, visualization of the data at different stages helps detect unexpected values or patterns. Finally, for complex pipelines, I will add logging statements and debugging points to trace the flow of data and identify the exact point of failure. Consulting online forums and documentation for specific tools is also invaluable.

Q 17. How familiar are you with different types of sequence alignments and their applications?

I’m very familiar with different sequence alignment methods, their strengths and weaknesses. Pairwise alignments, like Needleman-Wunsch (global) and Smith-Waterman (local), are fundamental for comparing two sequences, identifying regions of similarity and calculating scores reflecting evolutionary relationships. Multiple sequence alignments (MSAs), using tools like Clustal Omega or MUSCLE, are crucial for aligning several sequences simultaneously, revealing conserved regions important for functional analysis and phylogenetic studies.

For instance, pairwise alignment can be used to identify homologous proteins, which share ancestry, within a species or across species. MSAs are critical in phylogenetic studies, providing the input for constructing evolutionary trees and identifying conserved motifs in protein families. The choice of alignment method depends on the research question. Global alignments are suitable for highly similar sequences, while local alignments are better suited for detecting short conserved regions between distantly related sequences. The choice between pairwise and multiple sequence alignments is dictated by whether you compare two or more sequences.

Q 18. Describe your understanding of phylogenetic analysis and its use in interpreting database information.

Phylogenetic analysis is the study of evolutionary relationships between organisms or genes. It utilizes sequence data (DNA, RNA, or protein) and comparative methods to reconstruct evolutionary trees (phylogenies) which represent evolutionary history. Databases like NCBI and Ensembl provide sequences needed for such analyses.

For example, in a study focusing on the evolution of a specific gene family, I would retrieve sequences from UniProt or Ensembl for orthologous genes (genes in different species derived from a common ancestor) across various species. I would then employ tools like RAxML or PhyML to construct a phylogenetic tree based on the aligned sequences. This tree illustrates the evolutionary relationships between the genes, offering insights into gene duplication events, divergence, and functional evolution. The information derived from the phylogenetic analysis could be compared against gene annotations from Ensembl and UniProt to gain a more detailed understanding of the gene family’s evolutionary history and functional divergence across species. Inconsistencies between phylogenetic relationships and annotations may even hint at annotation errors requiring further investigation.

Q 19. Explain the concept of genome annotation and how it is represented in Ensembl.

Genome annotation is the process of identifying and labeling genes and other functional elements within a genome sequence. It’s like adding labels to a map to understand the features. In Ensembl, this annotation is represented in a structured way, including gene locations, predicted transcripts, exons, introns, regulatory regions, and protein-coding sequences. This annotation is based on a variety of evidence, including experimental data (e.g., RNA-Seq), comparative genomics (comparing to other genomes), and computational predictions.

Ensembl uses a sophisticated system to represent these annotations. They utilize a relational database model storing different aspects of the genome in separate tables linked through relationships. For instance, gene information might be in one table, transcript details in another, and exon coordinates in a third. These tables are interconnected through unique identifiers, allowing for efficient querying and retrieval of complex relationships. This structured approach makes it possible to obtain a comprehensive picture of a genomic region including genes, transcripts, regulatory elements, and their relationships. The Ensembl web interface and BioMart tool allow convenient access to this rich annotation data.

Q 20. How would you access and interpret data related to gene expression from a database like NCBI GEO?

NCBI GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) is a repository for high-throughput functional genomic data, including gene expression data from microarray and RNA-Seq experiments. To access and interpret gene expression data, I would first use the GEO website to search for relevant datasets using keywords related to my research interests (e.g., ‘gene X’ and ‘cancer’).

Once I’ve identified a suitable dataset, I would download the raw data (usually in a format like CEL files for microarrays or FASTQ files for RNA-Seq). For RNA-Seq data, I would then employ tools like Salmon or RSEM to quantify gene expression levels. This will generate counts representing the number of reads mapping to each gene. These counts are then normalized to account for sequencing depth differences. After normalization, I might use statistical methods in R (limma or DESeq2) to identify differentially expressed genes between different conditions or groups. The results might be presented as lists of genes with their adjusted p-values and fold changes indicating their significance and direction of change in expression. The GEO website also provides some basic data visualization tools, and I might integrate them with more advanced visualization methods within R (e.g., creating volcano plots or heatmaps).

Q 21. How would you use UniProt to identify potential drug targets?

UniProt is a valuable resource for identifying potential drug targets. My approach would involve a multi-step strategy. First, I would use UniProt’s search functionality to identify proteins associated with a disease of interest. I could also use keyword searches or use advanced search options based on functional annotations, pathways, or protein family information.

Then, I would filter the results to focus on proteins that are:

- Essential for the disease mechanism (e.g., involved in pathogenicity or disease progression).

- Druggable (possessing characteristics that make them suitable targets for drug development, such as having a well-defined active site or allosteric site).

- Highly conserved across species to minimise off-target effects (if targeting a protein in humans).

UniProt provides information like protein structure (if available), domain architecture, and known interactions which help assess druggability. Furthermore, using UniProt’s cross-references, I could also explore associated publications related to the identified protein targets and their interaction with other proteins. Finally, the combination of information from UniProt along with external databases and literature can help in prioritising the potential drug targets and assessing their feasibility for drug development. This is a preliminary step; further in-depth analysis such as molecular docking studies and experimental validation is necessary to validate potential drug targets.

Q 22. What are some ethical considerations related to accessing and using bioinformatics databases?

Ethical considerations in accessing and using bioinformatics databases are paramount due to the sensitive nature of the data involved – often containing personal genetic information. Key concerns include:

- Data Privacy and Confidentiality: Ensuring patient anonymity and complying with regulations like HIPAA (in the US) and GDPR (in Europe) is crucial. This involves anonymizing data wherever possible, using appropriate access controls, and adhering to strict data usage agreements. For example, a researcher might need to obtain informed consent before using patient data for a specific study.

- Data Security: Protecting data from unauthorized access, modification, or deletion is vital. Robust security measures, including encryption, access controls, and regular security audits, are necessary. A breach could have serious consequences, both ethically and legally.

- Data Integrity and Accuracy: Maintaining the accuracy and reliability of data is essential to prevent misleading or erroneous conclusions. This requires careful data curation, quality control checks, and proper documentation of data provenance.

- Data Ownership and Intellectual Property: Clearly defining ownership and usage rights is crucial. Many databases have specific terms of use that must be followed. Researchers must be aware of potential conflicts of interest and ensure proper attribution of data sources.

- Bias and Fairness: Bioinformatics datasets may contain biases reflecting the populations from which they were sampled. Researchers must be mindful of these biases and avoid perpetuating inequalities in their analyses and interpretations. For instance, a dataset predominantly representing one ethnicity might lead to inaccurate generalizations about other populations.

Ignoring these ethical considerations can lead to serious legal repercussions, damage to scientific integrity, and a breach of public trust.

Q 23. How familiar are you with data visualization techniques relevant to bioinformatics databases?

I am highly familiar with various data visualization techniques used in bioinformatics. The choice of visualization depends heavily on the type of data and the message to be conveyed. Common techniques I utilize include:

- Genome Browsers (e.g., IGV): For visualizing genomic alignments, variations, and annotations along the genome.

- Circos Plots: To represent relationships between different genomic regions or features, often used for visualizing chromosomal rearrangements or gene co-expression networks.

- Heatmaps: To display large matrices of data, often used to represent gene expression levels across different samples or conditions.

- Scatter Plots: To explore relationships between two continuous variables, such as gene expression levels and protein abundance.

- Phylogenetic Trees: To visualize evolutionary relationships between different species or genes.

- Manhattan Plots: Frequently used in Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) to highlight genomic regions significantly associated with a particular trait.

Beyond these, I am proficient in using tools like R (with packages such as ggplot2) and Python (with libraries like matplotlib and seaborn) to generate custom visualizations. The key is choosing the right visualization to effectively communicate the insights derived from the data. For example, a heatmap would be a better choice to show gene expression patterns across many samples compared to a scatter plot, which would be more suitable for examining the correlation between two variables.

Q 24. Describe your experience with programming languages used for bioinformatics data analysis (e.g., Python, R).

My experience with programming languages for bioinformatics data analysis is extensive. I’m highly proficient in both Python and R, having used them extensively in my previous roles.

- Python: I leverage Python’s versatility for tasks ranging from data manipulation and cleaning (using libraries like

pandasandNumPy) to statistical analysis (SciPy) and machine learning (scikit-learn). I also frequently use Biopython for sequence manipulation and analysis, interacting with databases like NCBI’s Entrez. - R: R is my go-to language for advanced statistical analyses and data visualization, particularly leveraging powerful packages like

ggplot2for creating publication-quality figures, andBioconductorfor tasks specific to genomics and bioinformatics. For example, I’ve usededgeRorDESeq2extensively for differential gene expression analysis.

My proficiency extends to writing efficient and well-documented scripts to automate tasks and conduct reproducible research. I understand the importance of version control using tools like Git and collaborating effectively through platforms like GitHub.

For example, a recent project involved using Python and Biopython to parse large FASTA files, align sequences using BLAST, and subsequently analyze the results using pandas to identify conserved regions.

Q 25. How would you design a database schema for storing and managing genomic variation data?

Designing a database schema for genomic variation data requires careful consideration of data types and relationships. I would propose a relational database model, leveraging a system like PostgreSQL or MySQL, with the following tables:

- Variants: This table would store information about each individual variant, including its chromosome, position, reference allele, alternate allele, and variant identifier (e.g., rsID from dbSNP). Data types would include

VARCHARfor identifiers,INTfor position, andVARCHARfor alleles. - Samples: This table would store information about the samples in which the variants are observed, such as sample ID, individual identifiers (anonymized), and metadata (e.g., sex, age, population). Data types would include

VARCHARfor identifiers and appropriate types for metadata. - Variant_Annotations: This table would link variants to their functional annotations, such as gene affected, predicted impact on protein function, and scores from prediction tools like SIFT or PolyPhen. This table would use foreign keys to reference both the

Variantsand relevant annotation tables (e.g., aGenestable). - Genes: This table would contain information about genes, including gene ID, name, location, and other relevant attributes. Data types would include

VARCHARfor identifiers andINTfor positions.

The tables would be linked using foreign keys to enforce referential integrity. Indexes would be added to key columns to optimize query performance. Data validation rules would be implemented to ensure data quality and consistency.

Furthermore, consideration should be given to adding tables for storing clinical information (if available), population data, and external links to relevant databases. The schema would be designed to be scalable and adaptable to future needs, allowing for easy addition of new data types and annotations.

Q 26. Explain the differences between public and private bioinformatics databases.

Public and private bioinformatics databases differ significantly in terms of accessibility, data content, and intended use.

- Public Databases: These databases, such as NCBI’s GenBank, UniProt, and Ensembl, are freely accessible to the public and contain a vast amount of publicly available biological data. Their primary goal is to facilitate scientific research by providing a centralized repository for data sharing and collaboration. Data submission often follows established standards and guidelines. Data quality is usually subject to some level of curation and validation but may still contain inconsistencies or errors. The data may be subject to terms of use which dictate how the information can be used and cited.

- Private Databases: These databases are owned and maintained by specific organizations or individuals, and access is typically restricted. They often contain proprietary data, such as results of clinical trials or internal research data, and are not publicly available. Access is often controlled through user accounts, access permissions, and usage agreements. Private databases are used for a range of purposes, from supporting internal research to developing proprietary products or services. Data quality is usually higher due to the tighter control over data entry and validation.

The choice between using a public or private database depends on factors such as data availability, data sensitivity, and the specific research objectives. Public databases are invaluable for large-scale studies and collaborative projects, while private databases offer greater control over data and are better suited for confidential or commercially sensitive data.

Q 27. Describe a time you had to deal with incomplete or poorly structured data in a bioinformatics database.

In a previous project analyzing cancer genomics data, I encountered a dataset with significant inconsistencies and missing values. The dataset, obtained from a clinical study, contained genomic variations from tumor samples but lacked consistent annotation across all samples. Some samples had detailed annotations about the types of variations, gene affected, and predicted effects, while others were sparsely annotated. Furthermore, there were inconsistencies in the sample IDs, making it challenging to track samples across different data files.

To address this, I first performed a thorough data cleaning and validation step. This involved identifying missing values and inconsistencies using Python’s pandas library. I implemented data imputation strategies, carefully selecting appropriate methods based on the nature of the missing data. For instance, I used mean imputation for numerical values where missingness was considered random and mode imputation for categorical values with a clear mode. For cases with missingness patterns which could not be suitably imputed, I carefully excluded the samples. I corrected inconsistencies in sample IDs and standardized the annotations using custom Python scripts. I carefully documented all data cleaning steps to ensure reproducibility and transparency. Finally, I generated summary statistics and visualizations to examine the cleaned data for potential biases introduced by the data imputation strategy.

Q 28. How would you ensure data integrity and consistency within a bioinformatics database?

Ensuring data integrity and consistency in a bioinformatics database is crucial for the reliability of any downstream analysis. My approach incorporates several key strategies:

- Data Validation: Implementing data validation rules at the database level (e.g., constraints, check constraints, and triggers) is crucial. This prevents invalid data from being entered in the first place. For example, ensuring that genomic coordinates are within the correct range for a given chromosome, or that allele designations are valid. Data type checking is also essential.

- Data Cleaning: This step involves identifying and correcting inconsistencies and errors in the existing data. This may involve scripting to identify invalid or missing data, then deciding on appropriate imputation or error correction strategies. This frequently involves leveraging Python or R tools.

- Regular Backups: Regular backups are essential to protect against data loss due to hardware failure or other unforeseen events. A version control system for database schemas can be helpful for tracking changes and reverting to earlier versions if necessary.

- Access Control: Restricting access to the database to authorized personnel only helps to prevent unauthorized modifications or deletions. Role-based access control (RBAC) is an effective method for managing user permissions.

- Data Provenance: Maintaining a detailed record of data origin, processing steps, and any modifications made to the data is crucial for traceability and reproducibility. This includes meticulously documenting data cleaning and imputation steps.

- Data Auditing: Regularly auditing the database for data quality and consistency issues helps identify and resolve problems promptly. This can involve automated checks for data anomalies or manual review of data subsets.

By combining these strategies, a robust system for maintaining data integrity and consistency can be established, ensuring the reliability and validity of research findings based on the data within the bioinformatics database.

Key Topics to Learn for Bioinformatics Databases (e.g., Ensembl, NCBI, UniProt) Interview

- Database Structure and Organization: Understand the underlying architecture of these databases, including how data is stored, indexed, and retrieved. Consider schema design and data relationships.

- Data Types and Formats: Familiarize yourself with common data formats used (e.g., FASTA, GFF, XML) and the types of biological information stored (e.g., gene sequences, protein structures, annotations).

- Querying and Data Retrieval: Master effective search strategies using various query languages (e.g., SQL, specialized database-specific query tools). Practice retrieving specific data based on defined criteria.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Learn how to analyze retrieved data, identify patterns, and draw meaningful conclusions. Consider statistical methods and visualization techniques.

- Data Annotation and Interpretation: Understand the meaning and implications of different annotation types, including gene ontology (GO) terms, pathways, and protein domains.

- Specific Database Features: Explore unique features of Ensembl (e.g., comparative genomics), NCBI (e.g., BLAST), and UniProt (e.g., protein interactions). Understand their strengths and limitations relative to each other.

- Practical Application: Consider how you would use these databases to solve real-world bioinformatics problems, such as identifying candidate genes for a disease, analyzing protein-protein interactions, or performing comparative genomic studies.

- Troubleshooting and Error Handling: Understand common issues encountered when using these databases and develop strategies to troubleshoot and resolve them efficiently.

- Ethical Considerations: Be prepared to discuss ethical implications related to data access, privacy, and responsible data use in bioinformatics.

Next Steps

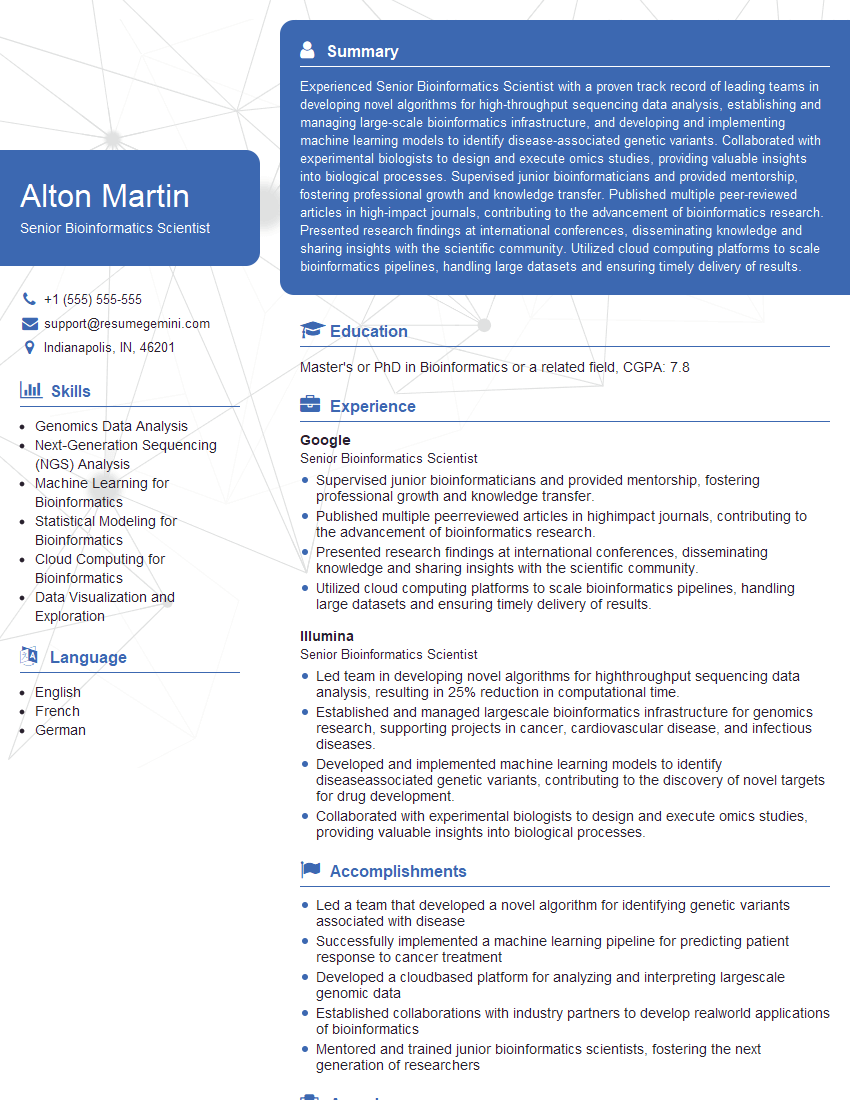

Mastering bioinformatics databases like Ensembl, NCBI, and UniProt is crucial for a successful career in bioinformatics, opening doors to exciting research and development opportunities. A well-crafted resume is your key to showcasing this expertise. To significantly boost your job prospects, create an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your skills and experience effectively. We recommend using ResumeGemini, a trusted resource, to build a professional and impactful resume. Examples of resumes tailored to highlight experience with Ensembl, NCBI, and UniProt are provided to help you create your own compelling application.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

hello,

Our consultant firm based in the USA and our client are interested in your products.

Could you provide your company brochure and respond from your official email id (if different from the current in use), so i can send you the client’s requirement.

Payment before production.

I await your answer.

Regards,

MrSmith

hello,

Our consultant firm based in the USA and our client are interested in your products.

Could you provide your company brochure and respond from your official email id (if different from the current in use), so i can send you the client’s requirement.

Payment before production.

I await your answer.

Regards,

MrSmith

These apartments are so amazing, posting them online would break the algorithm.

https://bit.ly/Lovely2BedsApartmentHudsonYards

Reach out at [email protected] and let’s get started!

Take a look at this stunning 2-bedroom apartment perfectly situated NYC’s coveted Hudson Yards!

https://bit.ly/Lovely2BedsApartmentHudsonYards

Live Rent Free!

https://bit.ly/LiveRentFREE

Interesting Article, I liked the depth of knowledge you’ve shared.

Helpful, thanks for sharing.

Hi, I represent a social media marketing agency and liked your blog

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?